Tags

American literature, edgar allan poe, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, nineteenth-century literature, poetry, Walt Whitman, women's education

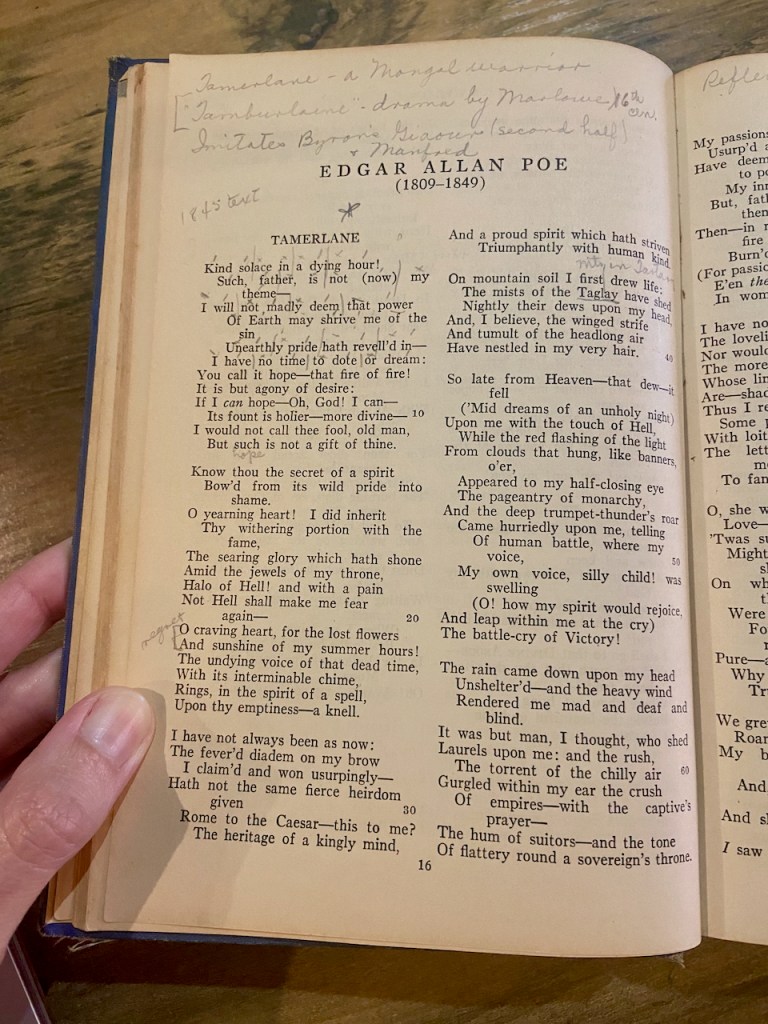

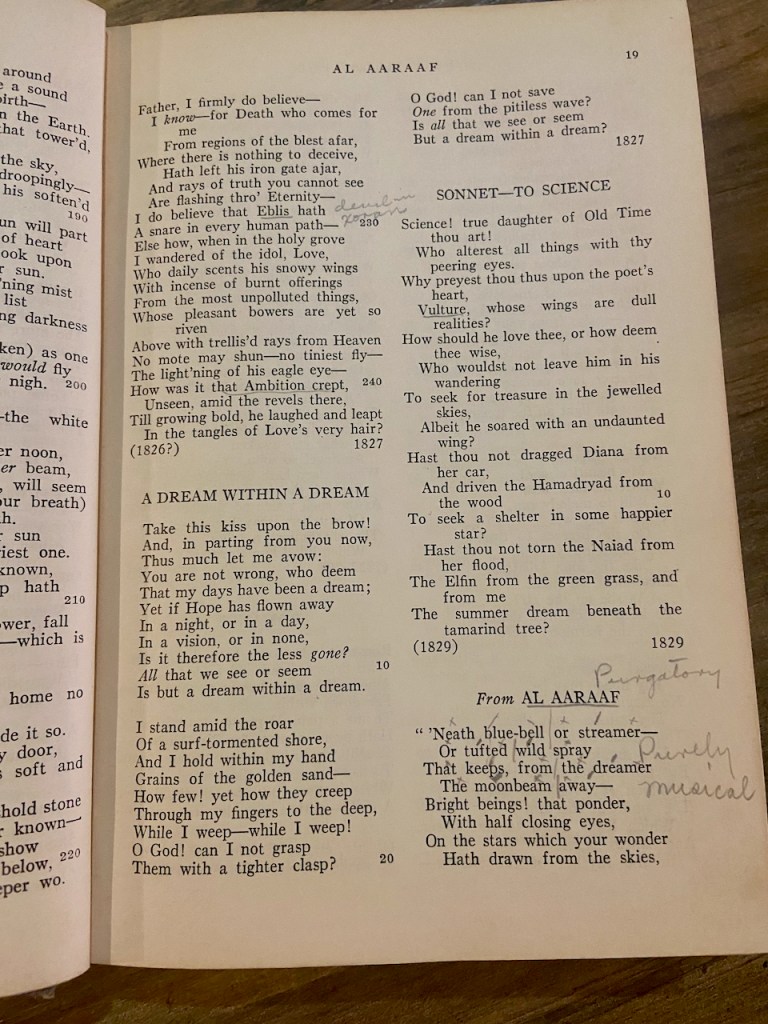

In my last post, I reflected on an American literature anthology published in 1935 and what the book’s secondary markings, table of contents, and editorial preface could suggest about its role in its place and time. My working hypothesis based on those elements is that this book was assigned as a textbook at UT Austin for an American literature course, perhaps a sophomore literature course, and that it was used by at least two students, one of whom was named Doris Grisham and took extensive notes throughout the text on the assigned readings.

I wondered how usual it was for a woman to attend college in the 1930s and 1940s. At its inception in 1883, 26% of UT Austin’s students were women. From what I could find on Wikipedia and other sources, this number grew steadily until today, when a little over half of college students enrolled are women. I even read on Wikipedia that doctoral degree-earning peaked for women in the 1930s and opened more fields for them. It seems likely that around 40% of students enrolled at UT Austin during Doris Grisham’s time were women. Thus, my stumbling across a textbook used by a female student does not have such a low probability.

When I left off on this post two weeks ago, I felt a little bit lost looking over those marked-up texts. It was fairly easy to guess that lessons had been supplied on the rhythm of the poetry, judging by the markings over stressed and unstressed syllables. I remember learning about the various rhythms poetry can take in high school. However, the lessons never took on much significance for me beyond mastering a skill for a test. I never grasped the significance of poetry in the 19th century and earlier, when rhythm and rhyme were such crucial elements. I knew the point of learning about rhythm and rhyme for the classroom was to earn a good grade and, more vaguely, to develop an educated appreciation for literature. I knew I loved literature, but did I love it or understand it in the same way that its original recipients did?

That question has been the focus of my musings for the past week, and my conclusion was, definitely not. I don’t think I’m able to conceptualize the popularity of poetry or the celebrity of poets except by comparing them to contemporary celebrities, which hardly seems like a fair or congruous comparison.

One article that gave me insight of these contexts was Jill Lepore’s “How Longfellow Woke the Dead,” published in The American Scholar in Spring 2011. Another was David Haven Blake’s “When Readers Become Fans: Nineteenth-Century American Poetry as a Fan Activity,” published in 2012 in vol. 52. no.1 of American Studies. My dives into these articles have left me two distinct ideas so far:

One, that poetry was for everyone. Poetry was read aloud in social or public gatherings and at life events like weddings or funerals. Rhythm and rhyme were elements that were important when poetry was spoken aloud and were elements that made poetry fun for children to read aloud. Poems were memorized and performed or chanted together. The themes of poetry were broad and universal, making them accessible to everyone. The intertextuality in poems, allusions to other works, made them stimulating and multidimensional to readers educated in classic literature and philosophy, or perhaps, in the absence of such an education, piqued the audience’s interest or allowed them to begin gathering impressions of them.

Two, that there was an intimacy in the words of a poet that may transcend the intimacy that contemporary celebrities project through their bodies of work, instilling emotions of intense passion in their audience. Poems were not necessarily meant to always be read aloud. Instead, many volumes of poetry were meant for private consumption, for dwelling deeply on what lines and phrases suggested about the poet’s experience, engendering the reader’s involvement and identification with the poet. Unlike contemporary celebrities, it was probably not possible to know exactly what a poet looked like or sounded like, or the specific details of their lives, though I get the impression that journalists did as much as they could to share this information, because there was so much public demand for it. Whitman received letters detailing explicit passion inspired in his readers, and Longfellow received surprise visits at his home from a variety of strangers who thought of him as a kind of public property.

I wonder if this sense of intimacy transcended contemporary parasocial feelings toward celebrities when poetry was read in the quiet that encourages free and deep thinking, and in the absence of any visual and aural counterparts of the writer, leaving the reader’s imagination to activate and strengthen over time toward literary pursuit.

To return to the margins of “Tamerlane,” I noticed that all of the extra-textual references recorded about Marlowe and Byron, as well as the poet’s relationship with Sarah Elmira Royster, were detailed in the biographical footnotes at the back of the book. This suggests that the book’s footnotes were taught directly as course material or that the book’s owner was studying it on her own. Since the footnotes cluster around the time-honored “masters” of American literature, though, I lean toward believing the former idea.

Speaking from experience, I find that intertextual references offer pleasurable insights into a text when I have actually read the work that is referred to; however, more often than not, I feel that creeping sense of a towering canon of literature that I should have read, and didn’t, and maybe didn’t even know about, and feel disconnected from the work that I am reading because it clearly wasn’t meant for me.

I guess that at least some nineteenth-century readers may not have read these works either, especially if they were educated in a more rural environment, and that the references did not present this kind of distraction because the readers were consuming the poetry as a force sympathetic with their own feelings.

I wonder what it would take to come to this kind of place again, in which a desire to connect with an unseen other is cultivated through words, intellect, and imagination, or if this poetry represents a brief cultural preoccupation with this imaginative play that will never been realized in humankind again.