Tags

American literature, American Romanticism, anthologies, antique books, archival theory, books, canon, canonical works, literature anthologies

There are a few classes I took in graduate school that opened my eyes to new ways of seeing books as three-dimensional objects. These classes taught me how much you can read from a book without reading the actual contents of the book. I have always been interested in collecting antique books, and these teachings gave me new ways to perceive the books I already have and also encouraged my collection habits, so that I always have at least one kind of old book I am looking for and studying.

One class that opened my eyes to this way of seeing books was Dr. Amy Tigner’s course on women’s early modern manuscripts. In this course, I learned about how texts were created and circulated in the 17th and 18th centuries, with a focus on women’s writing.

The most exciting thing I learned about in that class was the commonplace book, which was a personal blank book that individuals would inscribe with poems, quotes, and even personal entries connecting them with important figures. These books were meant to be shared in social settings. When I learned about them, I thought they sounded like a kind of precursor to a person’s social media page. The books could be personal and sentimental, or they could be created with an eye to shaping the individual’s image in the public eye.

One task I learned in this course was how to transcribe early modern handwriting. Some letters were different and spelling of words varied, even with a word used twice in the same sentence.

As a class, we transcribed (and cooked) early modern recipes from a cookbook of recipes collected and handwritten by a Englishwoman named Ann Fanshawe. Ann Fanshawe’s cookbook provided information about her social class, finances, and most interestingly, her travels to Spain. I could tell from studying the cookbook that Spanish culture was very trendy in her time.

Learning to analyze cookbooks, commonplace books, and diaries as physical, handwritten texts (accessed digitally, in our case) gave me a more objective lens with which to analyze books that was further augmented in Dr. Cedrick May’s course on archival theory.

Archival theory was a paradigm shift for me on both intellectual and material fronts. I learned how to properly check out archival materials from university libraries and archives and how to analyze paper contents productively, paying attention to small details about old photographs or what was written in the margins of a typewritten manuscript draft in search of telling an obscured or forgotten history.

These material forms of literary criticism gave me new eyes for my long-held interests in antique books and historical cemeteries and caused me to see meaning in artifacts all around me.

The course that convinced me of the importance of anthologies was Dr. Kenton Rambsy’s on African American short stories, particularly what I learned about the importance of selections for American literature anthologies or Black literature anthologies.

All throughout graduate school, towering over me was something called the “canon,” which was rarely mentioned but always there, a collection of so-called essential works that were baptized long ago by a magic wand. Long ago, when? Whose magic wand? When you start asking those kinds of questions, that’s when you are on to it. The weird thing about the intellectual community is that the “canon” still very much towers over you despite all of the questioning that goes on. I can feel ashamed about the things I should have read or paid more attention to but didn’t, even though I am not interested in them.

Dr. Rambsy’s class gave me an awareness of the idea of the “canon.” There are canonical American literary texts and within these, a canon of African American literary texts, which may be included in American literature anthologies. What is included or excluded matters a lot, not only because it is more likely to be what is read by the public, but it will also be what is taught in schools. It’s a simple idea that’s grasped in an instant, but spending a semester working with that notion gave me a new appreciation for questioning what texts are placed at the forefront and what are minimized or excluded.

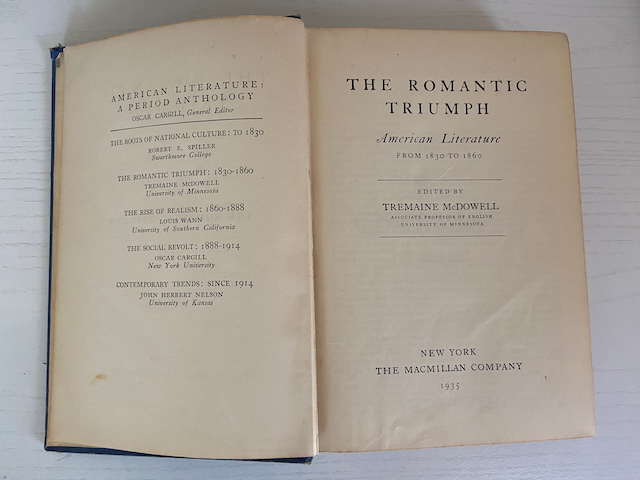

This review brings me to my American literature anthology published in 1935, The Romantic Triumph: American Literature from 1830 to 1860. These classes that I’ve briefly summarized gave me an appreciation for how deeply I can read and analyze this book before I even start reading any of its contents.

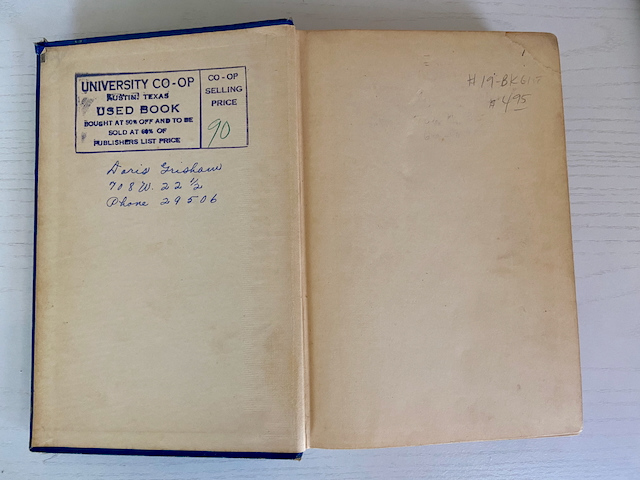

I am pretty sure I purchased this book at an antique store in north Austin, but it looks like it was previously sold by University Co-op. A quick web search yields the information that this business has been around since 1896 and sells course materials to UT Austin students, so I know this book was recirculated through this channel to be redistributed to one or more students for a literature course. And at least one of its owners was “Doris Grisham” (The name “Doris” peaked in the 1920’s and 1930’s in popularity). I see Doris’s handwriting on the margins on the pages and at least one other person’s. Some of the writing is in pencil, and some in nice-looking fountain pen ink (I learned that fountain pens, not ballpoint pens, were predominantly used during the 1930s when researching my observations about this book).

My initial question as I peruse this book is: why were these authors and selections chosen for this book? They were selected by Tremaine McDowell, Associate Professor of English at the University of Minnesota.

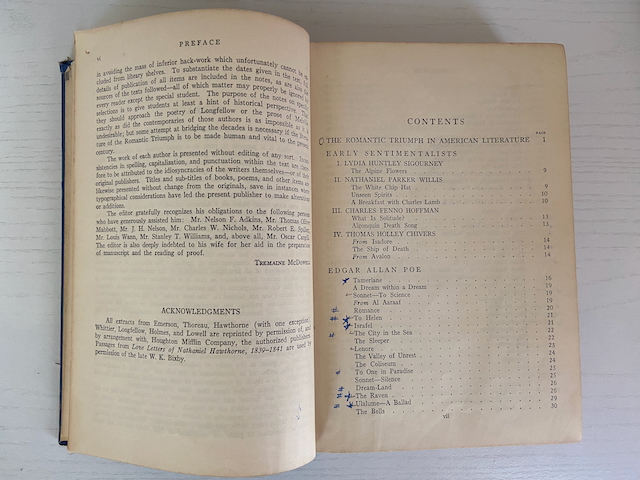

The book’s preface is intended to provide a justification and rationale for the editor’s selections. The first sentence reads, “The major purpose of this book is to give, from the prose and poetry of the American authors who flourished from 1830 to 1860, the most extensive readings which it is possible to print in a single volume of convenient size.”

What do you think he means by “flourished?” Is he referring to the most successful writers of these decades who flourished in terms of sales and popularity? Does he mean the writers that were most closely connected to the Romantic movement? Or just those that were “the best?” The last of these options is certainly the most subjective and puts a lot of power in the hands of this editor.

Two writers conspicuously absent are Emily Dickinson and Walt Whitman. Dickinson did not achieve literary fame during her lifetime, and it was only decades after her passing, particularly after a collection of her work was published in 1955, that she was considered an important figure in American literature. Walt Whitman, on the other hand, was a popular poet in the time period this anthology covers, but his work was probably considered too obscene or controversial to include in literary anthologies. While now, many professors like to teach and analyze the sex stuff.

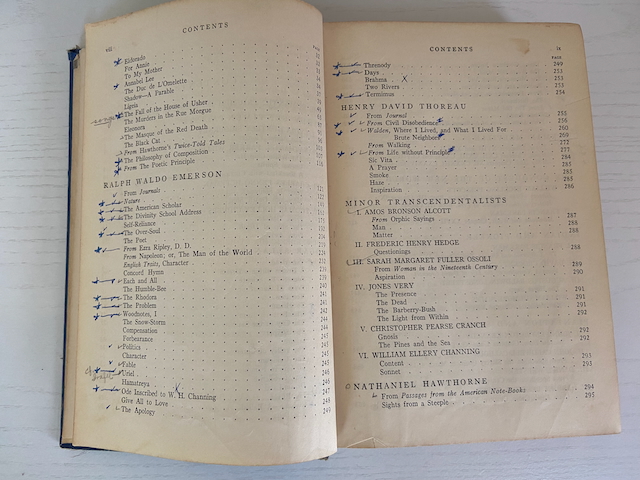

Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin was a very popular work in her time but only receives a small excerpt in this collection. Clearly, she is not considered among the “masters,” whom McDowell lists as “Poe, Emerson, and Hawthorne.” McDowell writes that “[i]mportant authors are presented separated as individuals; less significant authors are grouped to exemplify tendencies and movements…”

There are other writers that are “presented separated as individuals” that I am not as familiar with. I was assigned a couple of Whittier poems to read in graduate school in a Dickinson and Whitman-centered class, but definitely nothing by Longfellow or Holmes. This caused me to be interested in why these writers, clearly part of the “canon” at the time of this book’s publication, are no longer so essential 90 years later.

When I started to research this topic, I found some complex and interesting ideas. The answers I found were not what I had expected. I had expected to find that women writers and writers of color had replaced these once-canonical figures, but that does not seem to be the reason. The answer lies more in the realm of the tastes engendered by the “new criticism” era of literary criticism, when “sentimental” works are disdained in favor of the ironic, cryptic, or gritty “tasteful” literature. When I browsed in JSTOR, I noticed that discussion of Longfellow sharply dropped off after the 1950s. The most recent paper I saw on his work was from 2014, which would make it very hard to bring his work back into the discourse without writing criticism slanted as a kind of recovery project.

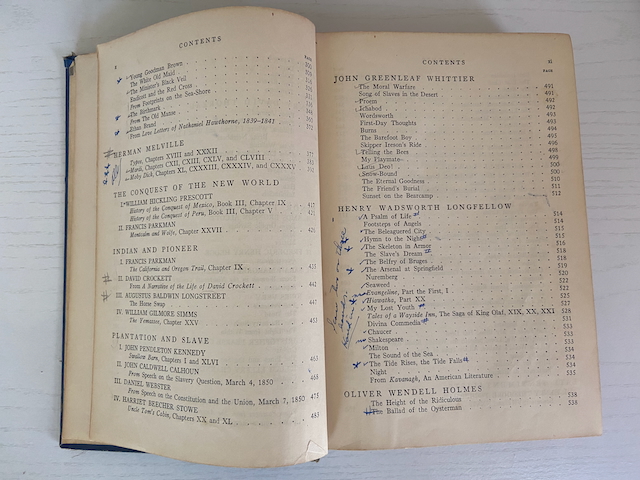

My next question is: what insights can I gain from the students’ annotations and markings on the pages of this anthology? In the table of contents, works by Poe, Emerson, Thoreau, Hawthorne, Melville, and Longfellow are heavily marked. All of these, with the exception of Longfellow, were writers extensively taught in my undergraduate literature classes, so it doesn’t come as much of a surprise. But chances are, these writers were read and taught very differently then than now. Each generation of thinkers, of course, decides what to emphasize, what to minimize, and what to ignore.

There’s a lot that’s been written on what was never included among the canonical texts in the first place. Some writers, like Dickinson, never achieved any degree of fame in their own day, or were even published. Other writers, like Edith Maude Eaton (pen name Sui Sin Far) may have been popular in their day, published in magazines or in a cheaper novel format, excluded from the “canon,” then “recovered” because their works lend insight to new schools of criticism.

What did the previous owner of my book, Doris Grisham, read, and what might she have thought about it? That’s my line of inquiry as I continue to study the annotations of this text.