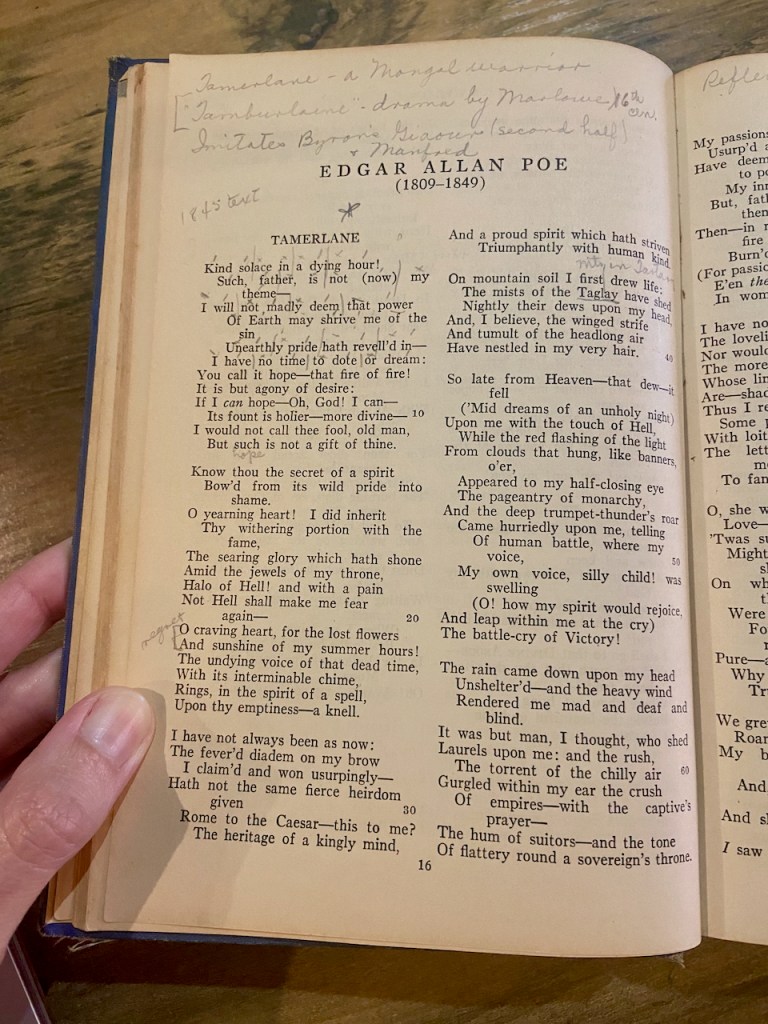

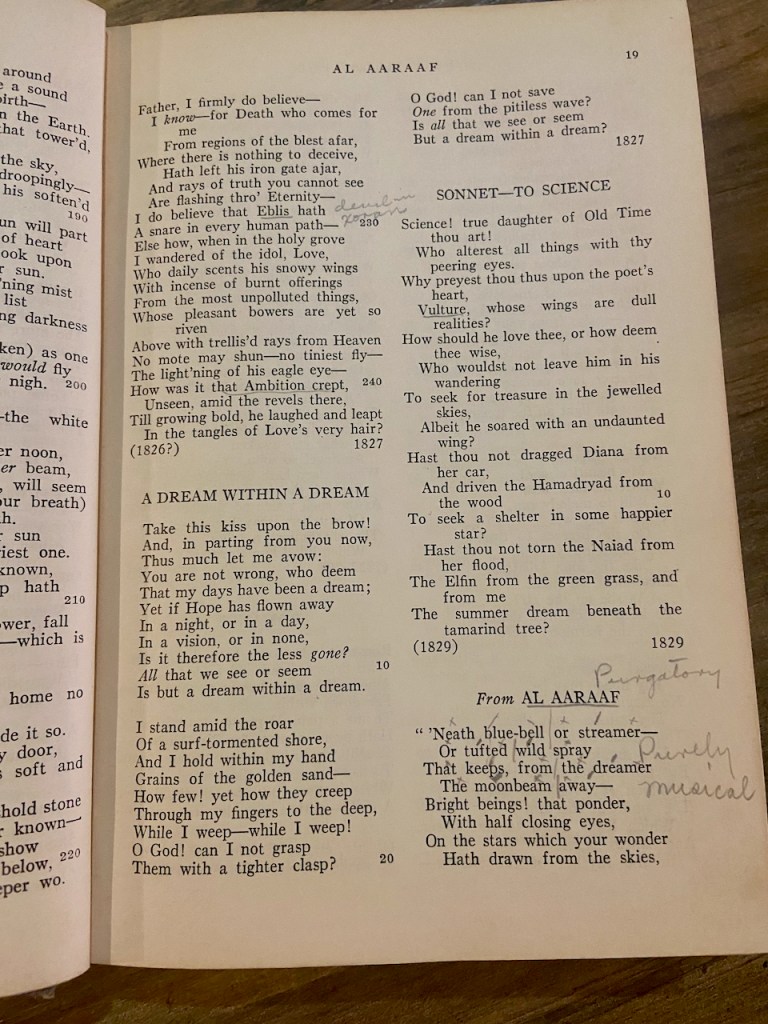

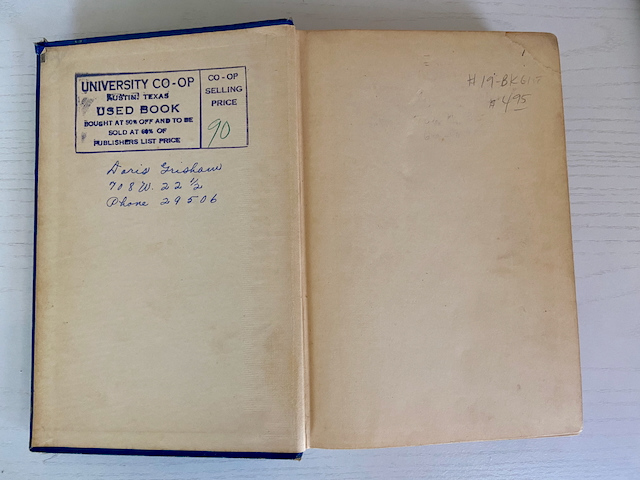

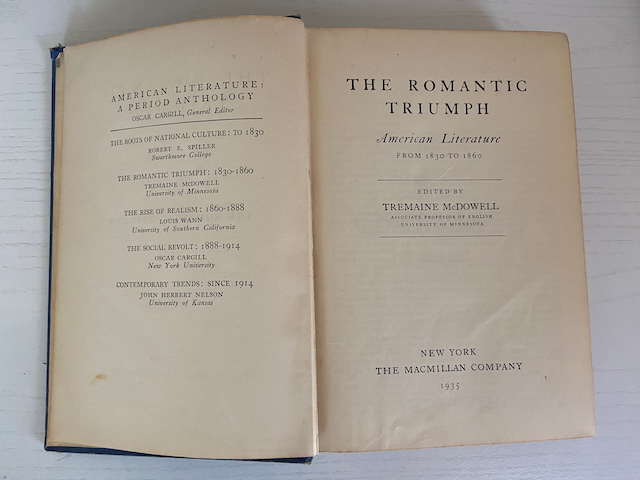

In my last post, I considered what it would be like to read Poe’s “Tamerlane” and other works by nineteenth-century “celebrity” poets as a student in 1935. I also considered, more silently, the imagination’s ability to reconstruct past scenarios, perhaps accurately, perhaps inaccurately. Inaccurate representations can be as valuable as accurate ones, because they tell us about the writer’s world, if not about the world they seek through imagination. Published histories tell us what was important to the writer and perhaps their audience at the time they were published. They may also tell us some things about the past, but as a student of archival studies will learn, histories are stories constructed from archival materials, interpretations of primary sources that inevitably favor some ideas and disfavor others.

I applied this kind of thinking to my re-reading of Charles Dickens’ 1851 essay “What Christmas Is as We Grow Older,” in how my own response to the essay prompts a series of questions about the world in 2025.

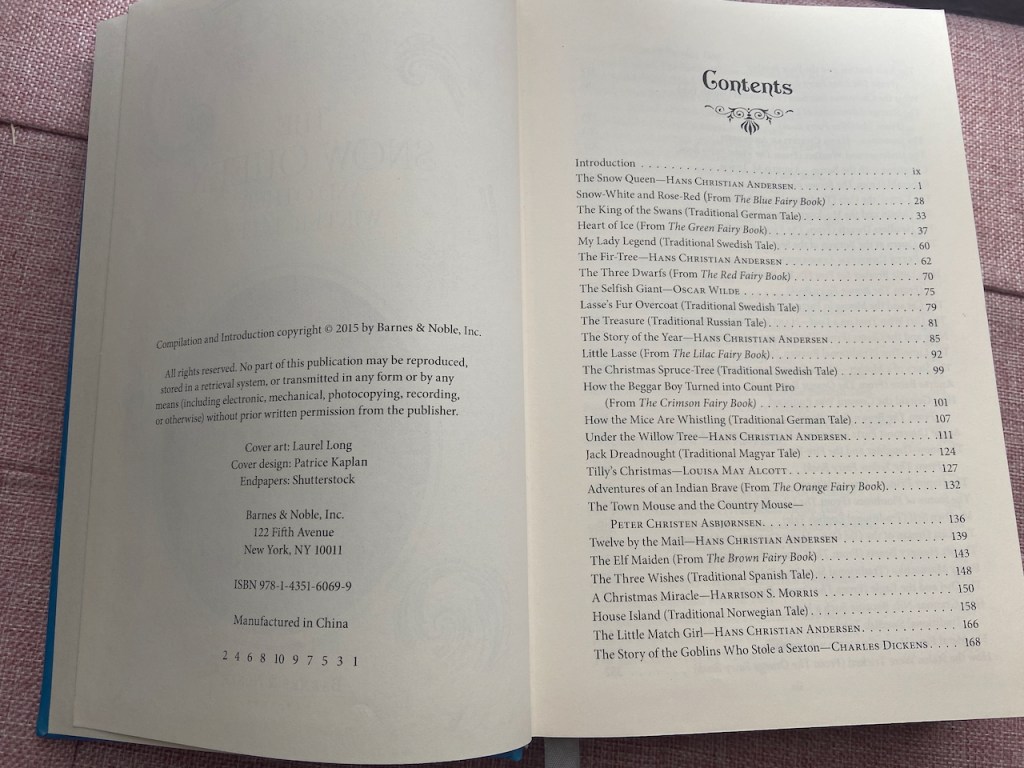

This essay is part of Barnes and Nobles’ 2015 anthology The Snow Queen and Other Winter Tales. The anthology, on the whole, communicates a darker tone than one might initially associate with the crystalline beauty of winter and the festivities of Victorian Christmases past. Dickens’ essay is far from the darkest work in the anthology. I think that falls to the writings of Hans Christian Andersen, whose stories in this anthology speak more about the cruelty of the wintry internal landscape of the human than the extreme hardships common folks experienced in the winter season prior to electricity and what we call modern conveniences (though the stories of that sort are thought-provoking to read as well).

Charles Dickens’ essay begins with a cynical and somewhat seemingly self-torturous recollection of Christmases-that-never-were, in convoluted sentences that I have to read at least twice over to fully catch:

What! Did that Christmas never really come when we and the priceless pearl who was our young choice was received, after the happiest of totally impossible marriages, by the two united families previously at daggers-drawn on our account? When brothers and sisters-in-law who had always been rather cool to use before our relationship was affected, perfectly doted on us, and when fathers and mothers overwhelmed us with unlimited incomes? Was that Christmas dinner never really eaten, after which we arose, and generously and eloquently rendered honor to our late rival, present in the company, then and there exchanging friendship and forgiveness, and founding an attachment, not to be surpassed in Greek or Roman story, which subsisted until death?

For the sake of Dickens’ wife at this time, Catherine Thomson Hogarth, who must have been quite busy birthing and raising the ten children he sired with her, while he was writing, I am hoping this was a hypothetical scenario, especially as it advances that the “pearl,” or longed-for woman the speaker was never able to marry, is compared to the present wife, “placider but shining bright — a quiet and contented little face” in which the speaker sees “Home fairly written.” The essay, rather, traces ideas of looking at a very early childhood Christmas, which “encircl[ed] all our limited world like a magic ring, left nothing out for us to miss or seek… grouped everything and every one around the Christmas fire; and made the little picture shining in our bright young eyes, complete,” then turns to view adolescence and young adulthood, when that wholesome picture becomes more fragmented, and Christmas becomes a time of longing for fulfillment rather than one of completeness.

Then, the essay lapses into what is for me, at least, some painfully sentimental prose about “a poor mis-shapen boy on earth… of which his dying mother said it grieved her much to leave him here, alone.” However, “he went quickly, and was laid upon her breast,” and subsequently, the tragedies of a young soldier dying “upon a burning sand beneath a burning sun,” and “a dear girl– almost a woman– never to be one” who “went her trackless way to the silent City,” are presented as objects to grieving relatives and acquaintances.

When I read the essay closely, I do not see what I had hoped to find, what I always hope to find in works from centuries past: a common thread of humanity binding us more closely than world events, technologies, and changing cultures can sever or distance. Sometimes I find this reassurance and take much comfort in it, but today I didn’t, somewhat repelled by Dickens’ sentimental gloss on suffering. Instead, I consider how many more conflicts the West has entered into “upon a burning sand beneath a burning sun” and otherwise (several in my lifetime alone), how head-of-household women and their children suffer due to inadequate medical care, and a variety of atrocities arisen in the last 174 years which have no equivalents in this essay.

The answer he presents in the face of the cruelties of present reality is one of remembrance: “You shall hold your cherished places in our Christmas hearts, and by our Christmas fires; and in the season of immortal hope, and on the birthday of immortal mercy, we will shut out Nothing!”

There is no doubt that, as we grow older, we will have experienced many more deaths, which lends perspective to life. But cultural epochs have gone and gone since Dickens and now. Namely, the rise of modernist thought, suspicious and cynical by nature, in the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-centuries, to give way to the postmodernists, and their successors, who still grapple with modernity’s darkness in factions so fragmented that it sometimes seems hard for one liberal line of thinking to meet another.

I think, whether we believe in Strauss-Howe generational theory, or not (and I can definitely see both sides of that argument), we do feel that we are plummeting quickly to the bottom of something. The consumerist nature of Christmas has escalated in the past two centuries so that I, for one, cannot conceive of it without its glittery excesses. As Western capitalism fails in an extraordinarily ugly demise, the glitter becomes a frenetic malaise of packages no longer delivered in one or two days or postponed and cancelled grocery deliveries (all of which, if we are being honest, we feel gross for purchasing in the first place), and of coffee shops that drive us out of a moment of respite with intentionally headache-inducing lights and music. The formerly great giants of retail famously killed off smaller fry once upon a time, to become wastelands of empty shelves mingled with shelves that look like a bomb went off in them. On observation, we find that some offhand household item or other we need is no longer sold in a brick-and-mortar shop at all. We wonder if the decor we hoped to find to beautify our spaces that looks so peculiar has been designed by AI. We log in to online platforms to catch glimpses of relatives or acquaintances that are all but completely lost beneath piles of endless streams of rage bait to which we never subscribed and whose algorithms we have not encouraged.

Modern life as we know it is enshittified, and we may feel ashamed to feel a sense of suffering over it, when surrounded by what we know to be real and profound suffering in the world. We do have the world of suffering in common with Dickens, even if we conceive of it and express it differently. Extreme poverty and sickness were not strange in Dickens’ era, nor were steep class divisions, and especially not the racialization of labor. In present-day America, we are experiencing these through a haze of AI-generated trash and a creeping awareness of the dearth of ethics possessed by those that puppeteer our lives with our dependencies.

It does not feel like Christmas radiance can be generated through taking a step back and a deep breath and thinking of those that have gone before that we carry with us in spirit. The present is just too present.